ELI AVIVI, IN HIS OWN UNIVERSE

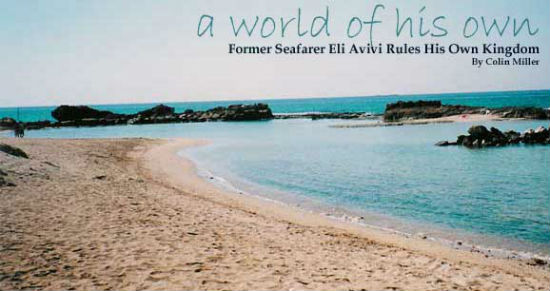

It could be a far-off region of Siberia or a country in Central Asia. The Mediterranean Sea gently laps at the shores of this self-declared autonomous state, which is located on the pristine northern coast of Israel. You have arrived in Akhzivland, Eli Avivi’s private domain.

A pair of blue iron gates stand out from the surrounding greenery just off the highway, where a sign stating “Eli Avivi” directs drivers’ attention. In 1952, Avivi arrived in this area for the first time. My sister was living in a community a few miles inland, so I traveled here to see her. I took a stroll down to the shore and discovered the town of Akhziv. “I fell in love with it and decided to make it my home,” Avivi adds. Nothing else was along this stretch of coast save from an ancient, deserted Arab home. Nothing was there.

The setting is spectacular and it has remained peaceful all day. To the north are the hills of Lebanon, to the east are the highlands of Galilee, and to the south, just 10 miles (16 km), lies Acre, one of the world’s oldest ports. Nothing but the pristine, blue Mediterranean Sea to the west.

Avivi is a symbol of the unconventional, free-thinking spirit that many Israelis find in him despite his colorful and unusual personality. This kind of thinking is becoming increasingly unacceptable in today’s society, which is rife with restrictions and mandates from on high. But then again, Avivi’s life hasn’t exactly followed the norm.

His Jewish parents brought him into the world in Iran in 1930, but the following year the family relocated to what is now Tel Aviv, in the area of Palestine governed by the British. I was a terrible lad who, together with several others, would try to obstruct British trains by laying objects on the tracks, he adds. There was a lot of turmoil in Palestine at the time because several Jewish factions were trying to get the British to give up their Mandate so they could establish a Jewish state. Avivi continues, “Many times we were caught by the British soldiers and brought before a court,” adding, “but my father knew the judge and we were only fined.”

In 1946, Avivi became a member of the so-called “Jewish Underground Navy,” which helped bring Jewish refugees from Europe to Palestine. Israel was founded after a civil war broke out between Arabs and Jews after the British departed the country in 1947. Avivi, however, was not yet prepared to give up her love of marine life. Following the war, I sought out new experiences by taking jobs aboard fishing vessels in the Mediterranean and the North Sea. Later, when bigger ships were available, I sailed to Iceland, Greenland, and Norway. Avivi explains, “It was quite chilly up there, and the going was extremely rough.

Avivi’s kind manner is at contrast with his notorious, daring history, as are his flowing white robe and soft spoken manner. He doesn’t seem his age (74), and he doesn’t have the stereotypically rough Israeli demeanor. He adds as he relaxes in the shade of his courtyard trees in the fresh sea breeze: “On one fishing trip in Northern Europe we were hit by a terrible storm and our ship was seriously damaged. We made it to a shipyard close to London, and I was able to see that fantastic city while the ship was being repaired.

Avivi, still in his early twenties, returned to Israel after more sailing expeditions to Africa. He hasn’t wished to live anywhere else since his first visit to Akhziv. He immersed himself in the local history (people have lived here since at least the Phoenician period, around a thousand years B.C.) and began amassing a wide variety of fascinating items. He has his own museum where he keeps his extensive collection of ceramics, stone tablets, swords, and tools. Many were discovered during deep sea explorations.

Avivi constructed his own home at a short distance from the water. Remembering the day when “I could fish from the window,” he says. In the early 1960s, he fell in love with and married Rina. Despite his ten years of residency in Akhziv, Avivi had no traditional legal title to the property. In essence, he was an illegal occupant. He believes he ought to be allowed to remain in the country because of the museum and house he built. And in this far-flung ‘border’ region, the law took a backseat.

However, things shifted in 1970. The government was able to get an injunction against him. “The authorities came with two bulldozers and leveled my house,” Avivi says matter-of-factly. He was so incensed at the moment that he called a massive press conference to make his case. He started receiving a lot of press. Anyone who would listen heard me rant about how much I loved Israel and how much I hated the government. All I wanted was the freedom to go about my life as I saw fit.

Thus, in the same year, Avivi proclaimed himself president of the brand new State of Akhzivland. “This way I can stay in Israel, but in my own country,” Avivi explains. However, the government wasn’t finished with him, and he soon found himself back in court. The judge was understanding, just like when he was a kid. Ultimately, “he threw out the action against me and said there was no case to answer,” as Avivi puts it. To this day, the legal status of Akhzivland remains unclear.